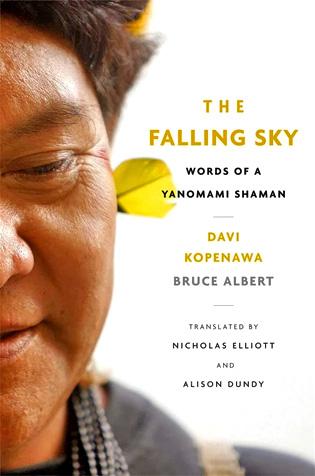

French anthropologist Bruce Albert’s book is a series of fascinating conversations with an Amazonian shaman that covers topics such as psychotropic drug use and the recent history of the Yanomami tribe

By Bradley Winterton / Contributing reporter This book, a prolonged labor of love by the French anthropologist Bruce Albert, is likely to become an important reference tool and possibly an instant bestseller. It mostly consists of discourses by an Amazonian shaman, duly noted down by Albert and then translated into French, and now English. The wider context — the status of worlds perceived while under strong psychotropic stimulation, and the recent history of the Yanomami tribe — is particularly fascinating.

This book, a prolonged labor of love by the French anthropologist Bruce Albert, is likely to become an important reference tool and possibly an instant bestseller. It mostly consists of discourses by an Amazonian shaman, duly noted down by Albert and then translated into French, and now English. The wider context — the status of worlds perceived while under strong psychotropic stimulation, and the recent history of the Yanomami tribe — is particularly fascinating.The extraordinary fact about the chemical dimethyltryptamine (DMT), the active ingredient of the bark of the tree the Yanomami call yakoana, as well as a wide range of psychedelic mushrooms and cactuses, isn’t merely that it occurs naturally in small amounts in the human body, concentrated in the pineal gland. What is even more sensational is that it appears to give rise, in whatever cultures it’s consumed, to visions of “little people”, what the Yanomami call xapiri, or dancing spirits. These are almost certainly what in other contexts have been dubbed fairies, elves, leprechauns, aliens or (quite possibly) angels.

Davi Kopenawa is no illiterate spirit-priest but the leading spokesman of the Yanomami, and recipient of several international awards. He began life learning Portuguese and later worked as a translator for a Brazilian government agency, and he’s subsequently visited France, the UK and the US to campaign for the rights of indigenous peoples. But he remains a shaman as well, initiated by his father-in-law at the age of 27.

The chapter describing this initiation is unforgettable. The yakoana powder was blown into his nostrils day after day, he fasted until his digestive system was entirely empty except for watered-down honey, he rolled on the ground, covered in dust and with his ribs sticking out, and still he couldn’t see the xapiri.

But then they came. “I saw them coming towards me from the sky’s heights in a shimmering white light … [They] arrived pressed tightly together in stunning lines, covered in body paint and colored feather ornaments.” Their clamor was loud and their songs melodious — “Arerererere!” — and they swirled and danced and whooped with elation when he answered them in a like manner.

There are only around 30,000 Yanomami, but they inhabit a large area of Amazonian rain-forest in the north of Brazil and southern Venezuela. They’re relatively well-researched as Amerindians go, and there’s even a 2000 BBC television documentary on YouTube, Pipe Dreams, in which the presenter takes a Yanomami youth on a trip to the UK, managing to acquire him a Venezuelan passport when, having no birth-certificate, he officially didn’t exist.

The Falling Sky, though, tells a sadder story. First is the frequent death from diseases brought by contact with whites — measles, flu, whooping-cough, rubella. Then comes the attempted construction of a major through-road in the early 1970s, the Perimetral Norte, later abandoned. Lastly there’s the influx of large numbers of illegal gold prospectors, beginning in 1987 and culminating in the Haximu Massacre of 1993 in which at least 16 Yanomami were killed.

Albert was employed as a translator at the trial of the 23 gold prospectors originally charged for this, and Kopenawa attended as a Yanomami representative. Five were sentenced to jail terms, though none were immediately imprisoned. Two were eventually jailed. More importantly, the killings were officially characterized as “attempted genocide,” a first in Brazilian legal history for the murder of Indians.

This book will for many take its place among other classics of the Amazon — Claude Levi-Strauss’s 1955 book Tristes Tropiques, for example, (Levi-Strauss befriended Albert and oversaw this book prior to his death, aged 100, in 2009), or Werner Herzog’s 1982 film Fitzcarraldo, with its accompanying documentary Burden of Dreams.

After reading this book, many images remain in the mind. There’s the angry white man who wants to marry a Yanomami teenager and is repeatedly refused permission, after which he unleashes an infection among the villagers via an improvised land-mine, with many consequent deaths. Then there are the Yanomami funeral rituals, in which the dead are cremated, their bones ground into a powder and either buried near the family hearth or consumed in a banana-flavored soup.

The desire of the Amerindians and their white supporters to protect the great rain-forests of South America has now become part of the wider ecological movement’s push to preserve the resources of the planet as a whole. But for those involved in the making of this book it’s something more specific, the urgent need to save the integrated range of the Yanomami lifestyle, from their living entirely on local resources without succumbing to the white man’s acquisitive “merchandise culture,” through their social relationships, to their entire cosmology, spirits dancing down beams of light included.

In North America these ancient systems have been all but lost except among some isolated Inuit communities. In South America, by contrast, such things might yet be saved. But, as Herzog has commented, currently “we’re losing riches and riches and riches.”

Many virtues lie half-concealed here, despite the picture popularized by Napoleon Cagnon’s 1968 US best-seller Yanomamo: The Fierce People of the Yanomami as dangerous warriors. They do fight, but they refused to avenge themselves on the murderous gold prospectors, for instance, as they considered them unworthy opponents because they didn’t possess a warrior’s code of honor. Also, Yanomamis esteem individuals for, among other things, how much they give away, not for how much they possess.

Are we looking here at noble savages, ecological pioneers, primordial visionaries or deluded drug-takers? Whatever the answer, the preservation of their way of life is part of the preservation of the human heritage, and not only in South America. These people probably migrated to the Amazon 20,000 years ago over the Bering Strait from Asia, and the origins of their traditions may therefore lie a good deal nearer home than we might be inclined to think.